Chapter 2 Conceptual framework

2.1 Open problems / features to consider

Open problems and features are are conceptual and ‘implementation’ issues that the system has to address in one or another way or at least provide a potential to do that. There is not particular order to the listed items now and they will be updated as the work progresses.

2.1.1 Representation / theory of value

In monetary exchange, the value of items is represented in a ‘flat’ and ‘one-dimensional’ way – in terms of money – which abstracts away subjective differences in how heterogenous agents value the same items of exchange. The main idea of Offer Networks is to allow for these subjective values to be (partially) externalized in a distributed marketplace in order to enable peer-to-peer exchanges. This should increase the total generation of value as compared to monetary markets which support consumerist dynamics. Yet the theory of value goes beyond purely Offer Networks concept and implementation.

Usually theories of value try to posit some sort of globally accepted measure of value, existence of which alone facilitates the exchange of goods – giving rise for transactional role of money. Yet the notion of global measure of value automatically takes away the subjective values and local aspect of exchange – precisely the things that Offer Network is supposed to bring back.

In any case, expression and communication of subjective values will involve some sort of simplification (in terms of map, vector representations or just behavioral preferences) which will need to be experimented with in a simulation model.

2.1.2 Description of items of exchange

Whatever will be exchanged in the market will have to be somehow represented and stored in a system for subsequent search and discovery by other agents. This is obvious but not simple, taking into account that every agent may ‘want’ to express its subjective preferences regarding concrete item offered / demanded. Ways to represent items could be:

- Limited number of hard-coded types. Obviously simplest to implement (and, depending on the angle of simulation, could be practical for the start), yet less realistic for a full fledged Offer Networks system.

- Natural language descriptions (or at least structured natural language). This seems to be most realistic, but also hardest to implement, as would need some sort of NLP capabilities on behalf of agents. The advantage is that it would allow seamless interaction of humans with the system (see HMI).

- Vector representations. A sort of a middle ground between natural language and hard coded types; I am currently in favour of this one, since it allows to define a simple similarity measure between items within exchange – allowing also to map them with ‘fuzzy’ or ‘incomplete’ preferences – which is an essential and necessary feature of the system;

- Real numbers can be a practical solution for experimenting with the system because they are easy to generate, store and require only basic mathematical functions for calculating similarity (see more)

- Map representations. The problem with vector representations is that they will require a sort of global key map for the values in a vector. In a map representation, and agent could explicitly indicate keys and their values. The similarity calculation may become somewhat more complicated in this case. Sparse Distributed Representation (of HTM) (Ahmad and Hawkins 2015). Just an idea so far, but could be interesting to explore.

2.1.3 Similarity measure

It should be possible to calculate similarity measures between items traded and their values (which is by the way not the same, taken into account emphasis on subjective values in Offer Networks…). This is where [representation / description of items of exchange] becomes important. The need of similarity measure also becomes important if taking into account incomplete preferences and selection for relevance of agents – they will somehow will need to find items that map to those incomplete preferences.

2.1.4 Matching algorithm and search

Given a (potentially huge) set of agents with {demand, offer} pairs, where demands and offers are items represented in a chosen way (see representation of items), an atomic task of an Offer Network at any point of time would be to find the items demanded by some agents which are offered by other agents and swap them so that the value created for agents participating in an exchange increases. For the problematics related to the ‘total value’ see discussion on centralization / decentralization which is not directly related to the matching algorithm / search (except that matching algorithm itself is related to it…;). For the problematics of the very ‘search’ problem in Offer Network, see incomplete preferences / selection for relevance. Possible matching / search algorithms:

- Proposed in (B. Goertzel 2015a) by ben@singularitynet.io:

- Reducing the ON Matching problem to Weighted Boolean Optimization / MaxSAT;;

- Mapping ON Matching problem into OpenCog Atomspace and solving with the Open-WBO/MaxSAT solvers on it;

- Proposed, formalized and experimented with in (Goertzel 2017) by Zar Goertzel:

- Maximum Edge-Weight Matching (MAX-WEIGHT)

- Maximum 2-way Matching (MAX-2)

- Greedy Shortest Cycle (GSC)

- Dynamic Shortest Cycle (DYN-SC)

- Hanging ORpairs (HOR)

- Proposed in [unpublished] by kabir@singularitynet.io:

- Aggregation of distributed vertex-based computations on a graph (see Computational framework for details)

2.1.5 Incomplete preferences and selection for relevance

In any close to realistic scenario agents cannot have complete and full preferences about everything what they demand / want (surely not if agents are humans) as well as an item of exchange cannot be represented completely and ‘non-ambiguously’. Furthermore, and more importantly conceptually, incomplete preferences of agents actually allow for communication, interaction, coordination and emergence rather than prevent it. Therefore allowing for incomplete preferences and foreseeing the mechanism of negotiation / individuation of incomplete (or in extreme cases – completely non-existent) preferences of interacting agents into behavioral choices is an essential aspect of a system aspiring for self-organizing dynamics. See The resolution of disparity in (Weinbaum (Weaver) and Veitas 2017) for a conceptual treatment of this aspect.

The important implication for Offer Networks is that ‘matching’ of demands and offers or ‘finding’ chains of exchanges among several agents is actually not at all a search problem given the space of possibilities ({offer, demand} pairs) but rather the result of dynamic interaction / negotiation among agents, in which concrete preferences / behaviours (not present before interaction) emerge from incomplete preferences, disparities and partial (in)compatibilities. The former (search) is a special case of the latter (negotiation) and the system architecture should at least attempt / consider the general case / framework before delving into implementation of special cases – which are nonetheless important.

The main centralization / decentralization issue is that in decentralized system there is no universal way to define relevance of items to all participants of the system (provide ‘best’ measures, ‘best’ reputation systems, etc.). Heterogeneous participants / agents will have different preferences and will select different aspects of the same item as important / unimportant to them – so will base decisions on a mechanism called selection for relevance. Consider also, that for any non-trivial agent the enacted preferences depend on the specific situation (e.g. Fido-dog agent built with OpenCog had a parameter ‘pee urgency’ which influenced its decisions…:)) as well as these preferences are incomplete in the first place. The implication is that preferences of agents can be identified and enacted only in the actual interaction of agents in the network and not prior to that. Anything beyond this (e.g. positing a global search mechanism / algorithm which chooses what is best for each agent based on their pre-announced preferences) is a movement towards centralization of a system – which may be needed or even desirable provided that limitations and advantages are wholly considered.

2.1.6 Human-machine interface

The vision of Offer Networks as an alternative economy first and foremost is concerned about increasing the welfare of humans and enriching ‘their’ economies (B. Goertzel 2015b, 3). Therefore human participation should be considered in the design of the system, albeit most probably not in early experiments. Leaving aside technical issues of the interface this presents at least two more conceptual issues/challenges: 1) Representing human preferences is tricky. It is obviously related to the representation / theory of value and description of items of exchange issues as well as Incomplete preferences and selection for relevance. 2) Humans will not participate in the system that asks them to list more than a few of their preferences (even if they know them for sure which is often not the case) about demands and characteristics of offered items. The SingularityNET-type solution seems to be to populate an Offer Network with AI agents representing preferences of people and having ability to interact with them in order to learn those preferences – and that would be a basis for Human-Machine Interface (see Conceptual architecture further in this document).

2.1.7 Centralization / decentralization

We use the following definition of decentralization: a system is decentralized if no agent has an ability to directly access the global state of the system. This does not prevent it to indirectly infer or collect the information about the system that allows to construct a representation of a global state (like Google does with Internet :);

Likewise, a centralized system is where a single agent (or agents) have a privileged role to access a global state of the system, collect information about it and provide such ‘global unified view’ to the other agents in the system (almost like Google does with Internet :));

Google’s example fits to both definitions which is the result of ‘rich becomes richer’ network dynamics illustrating that an initially decentralized system (Internet) can become centralized by merely a self-organized process (preferential attachment network dynamics). It also illustrates that in reality there are no strict borders between centralized and decentralized systems – they form a continuum (see here for more.

Suppose that a system initially consists of completely homogenous (in terms of knowledge/degree of connectivity and processing capacities) agents which are trying to find best ‘friends’ in the network. If these agents are autonomous, sooner or later some of them will turn out to be more successful so other agents will start finding ‘friends’ through them – they will become Facebooks and Googles of the SingularityNET – this dynamics is general for any self-organizing system of autonomous agents.

Note, that without such mechanism, complexification, evolution and learning in and of a system is impossible. On the other hand, when a few agents become so powerful that they start to influence decisions of majority of other agents in the network, the availability of diversity of the network decreases – and that again prevents complexification, evolution and learning. Furthermore, self-organization and search is a resource hungry process, therefore we want some sort of mechanism which propagates successful strategies/knowledge that can be utilized by others. Furthermore #2, the preferred balance between centralization / decentralization (degree distribution in a network if you will) depends on specific challenges and environment that the system is being exposed to. E.g. in stable times it may be globally beneficial to have more centralization and utilize / share a few best patterns of behavior, yet during volatile times it may be instrumental for the overall survival / stability of the system to experiment more (so destroy centralized hierarchies / neglect the highest degree nodes, etc.).

Bottom line is that an ideal system capable of evolving and learning should not be centralized or decentralized, but it has to dynamically find a way to combine two modes of operation and fluidly change their balance depending on circumstances. The conceptual problem is that internal ‘rich becomes richer’ dynamics is natural to decentralized systems / networks, yet the dissolution of centralized networks is not – it usually has to come from external sources with a threat to destroy the system… (see processes of integration and disintegration in (Veitas and Weinbaum 2015) for more).

This discussion provides a few guiding principles for the architectural design: 1. It has to be flexible enough for implementing, testing and evaluating many different centralization / decentralization mechanisms and behaviors (in terms of Offer Network – matching algorithms, representations and other features mentioned in this section); 2. It has to allow for variety (at least in principle if not from day one) in the system so that to allow agents themselves to have a say about the preferred / best matching algorithm, reputation system, representation, etc. 3. The system has to be able to learn / spread new useful patterns and to forget old or not-useful ones fast. The ideal criteria for a successful system would be its fluidity in adapting (learning new and forgetting old) rather than optimality / efficiency with respect to a static situation (while it could be an aspect to consider too); The goal of the architectural design is to express / operationalize these principles in computational terms and build a simulation environment / framework to experiment with them – which is the topic of computational framework.

Note also that from the computational standpoint, centralized algorithms are almost always more measurably efficient than decentralized for a simple (yet fundamental) reason that self-organization and resolution of disparities need additional resources (of time and memory). Finding clear cases, especially lending themselves to computer simulations with efficiency criteria that could give justice to Offer Networks distributed system is far from trivial and requires a rich simulation framework.

2.1.8 Memory / learning: emergence of identities

A system that learns has necessary to have a memory in order to be able to remember (and forget) patterns. For a network of agents (including Offer Network and SingularityNET) such memory is a connectivity pattern among them. If a network of collaborating agents find an efficient way to pool their resources / competences and to solve complex type of problems together that cannot be solved individually it represents a new pattern. If this pattern becomes persistent, conceptually it can be viewed as a kind of ‘super-agent’ – so a new emerged identity in the network.

For the conceptual treatment of the process see A descriptive model of the individuation of cognition (Weinbaum (Weaver) and Veitas 2017). In Computational framework part we try to see if a computational framework able to support this process and still be practically testable / usable can be conceived and implemented.

2.1.9 Storage of value / timed exchanges

In the specific case of Offer Networks, memory (apart from persistent connectivity patterns) is the ability to store value by agents (represented in reputation / tokens, etc.) for the usage later in timed exchanges. This is an essential aspect of the system and has to be considered in the early design (if not in early implementations).

2.2 Conceptual Architecture

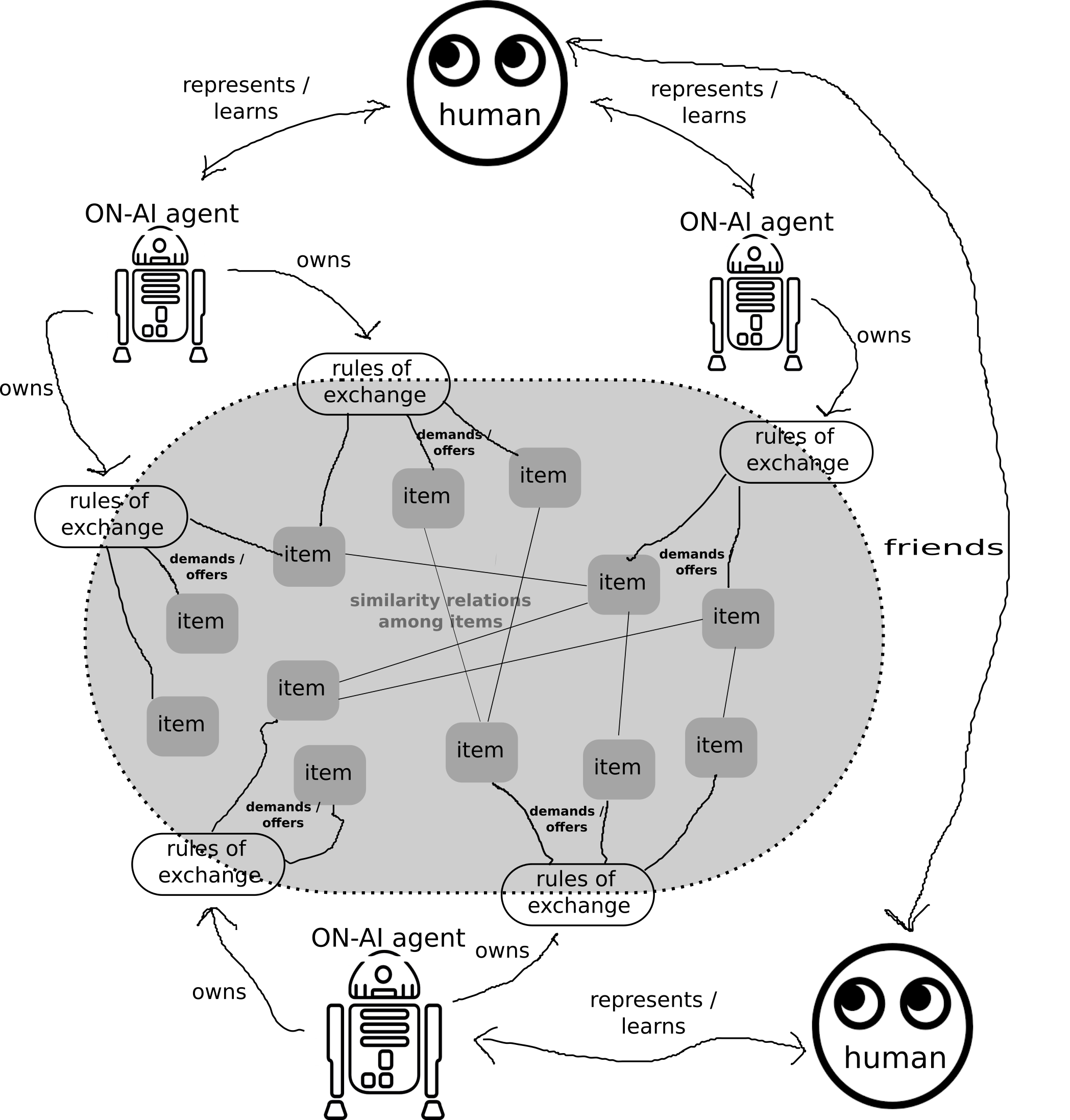

Taken into account all Open problems / features to consider the proposed conceptual architecture of Offer Networks is summarized in the picture below. The goal of simulation modelling is to experiment and test more or less isolated aspects of this architecture taking into account the future need for eventual integration of the results into the complete framework.

Figure 2.1: Conceptual architecture of OfferNet

In this architecture, the Offer Network consists of humans, which are represented by one or more ON-AI agent, which learns the behavior/preferences of the represented human relevant to its role in an Offer Network. An ON-AI agent formulates and owns sets of rules of exchange == conditions of how items (owned by the human) are offered and demanded in the network. Items are represented in a way that allows to calculate their similarity and match most similar items (i.e if an item1 offered by agent1 is sufficiently similar to item2 demanded by agent2 then there is a high probability that it is a match and the exchange can be executed. In case the similarity is not perfect (in real scenarios this will be always the case), the differences and incomplete preferences have to be resolved via negotiation of respective ON-AI agents with or without human intervention if AI agents cannot solve the issue themselves – implying more complex information flows within the network than just passing commands of humans to AI agents and then network.

We may also consider that humans that form the ‘outer’ layer of the network form a social network by knowing each other outside the Offer Network. This fact allows for distributed operation of the network without central authority – humans would join the network only via recommendations of friends. This social network could also be a basis for the distributed reputation system where reputation of an agent would depend on the reputation of its friends in Page Rank / Google Guice style. Of course the initial social network would be augmented by a social network between ON-AI agents on the basis of their operation already within Offer Network. The social network structure is important for distributed search of similar items, since (provided that the ‘small-world’ structure) every agent of the network can potentially reach every other agent in the network via small number of links1.

The efficiency of the operation of the network depends not only on the ‘smartness’ of ON-AI agents, but also on the structure of the network. The conceptual model does not prevent for introduction of additional ‘governing’, ‘matching’ or ‘similarity search’ agents operating on the same data structure.

2.3 Performance measure

Measuring ‘performance’ of the network of heterogeneous agents each having subjective values and running different processes without resorting to some sort of over-simplistic average (like amount of money or reputation at the end of the simulation) is a tricky issue. Yet we need some kind of ways to distinguish successful simulations from unsuccessful ones. Possibilities are listed below:

- Proposed, formalized and experimented with in (Goertzel 2017) by Zar Goertzel:

- (TM): Total number of ORpairs satisfactorily matched.

- (WT): Average wait time of ORpairs that are matched.

- (AMS): Average number of matches accepted / suggested matches.

- (SMS): Average size of suggested matches.(PoD): Matched task popularity measured by average product of degrees

- (TH): Total number of ORpairs held.

- (HT): Average number of times a hanging ORpair is held.

- (HWT): Max wait time of a user in a held node

- Proposed and (to be) experimented with in [unpublished] by kabir@singularitynet.io:

- (Static performance): Time required by the network to find known-to-exist matches in the network which are pre-calculated in advance;

- (Learning rate): Time required by the network to find subsequently injected known-to-exist matches;

2.3.1 Information integration

Conceptually the most interesting potential measure of performance of the network is information integration Φ, proposed by (Edelman and Tononi 2000). Φ formally defines coordinated clusters in networks of interacting agents across time and space and is used by (Tononi 2004) in developing an integrated theory of consciousness. Intuitively, “[a] subset of elements within a system will constitute an integrated process if, on a given time scale, these elements interact much more strongly among themselves than with the rest of the system” (Edelman and Tononi 2000, 135).

Such measure could in principle allow to detect the emergence of ‘higher scale agents’ in the self-organizing network (see Memory / learning: emergence of identities) and goes far beyond Offer Networks as could be an overall measure of measuring intelligence – which would be fascinating to experiment with on Offer Networks in simplified manner (and SingularityNET for that matter).

Measuring information integration of a dynamic network of heterogeneous agents adds another layer of complexity to the simulation, as the calculation of information integration may take considerable computational resources (potentially more than simulation itself…). While this is an interesting avenue to explore in the context of AGI research it is not currently considered in Computational framework.

References

Ahmad, S., and J. Hawkins. 2015. “Properties of Sparse Distributed Representations and Their Application to Hierarchical Temporal Memory.” ArXiv E-Prints, March. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2015arXiv150307469A.

Goertzel, Ben. 2015a. “Matching Algorithm for Attention Offer Networks.”

Goertzel, Zar. 2017. “Offer Networks Simulation and Dynamics.” Master’s thesis, Copenhagen. https://github.com/zariuq/offer-network-thesis/blob/master/Thesis/Zar_Thesis_Offer_Networks.pdf.

Weinbaum (Weaver), David, and Viktoras Veitas. 2017. “Open Ended Intelligence: The Individuation of Intelligent Agents.” Journal of Experimental & Theoretical Artificial Intelligence 29 (2): 371–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/0952813X.2016.1185748.

Goertzel, Ben. 2015b. “Beyond Money: Offer Networks, a Potential Infrastructure for a Post-Money Economy.” In The End of the Beginning: Life, Society and Economy on the Brink of the Singularity, edited by Ben Goertzel and Ted Goertzel, 1 edition, 522–54. Humanity+ Press.

Veitas, V., and D. Weinbaum. 2015. “Living Cognitive Society: A ’Digital’ World of Views.” Submitted to: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, October. https://vveitas.files.wordpress.com/2015/11/paper2.pdf.

Edelman, Gerald M., and Giulio Tononi. 2000. A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination. Basic Books.

Tononi, Giulio. 2004. “An Information Integration Theory of Consciousness.” BMC Neuroscience 5 (1): 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-5-42.